Carbon removals: the secret to reaching net zero emissions

Europe plans to drastically cut its emissions to reach climate neutrality by mid-century, but there is another weapon in the battle against global warming that policymakers say will also be essential: carbon removals.

The idea is to reduce the level of CO2 in the atmosphere and counter any emissions that remain after 2050 by taking carbon out of the air and storing it in nature or using technological solutions.

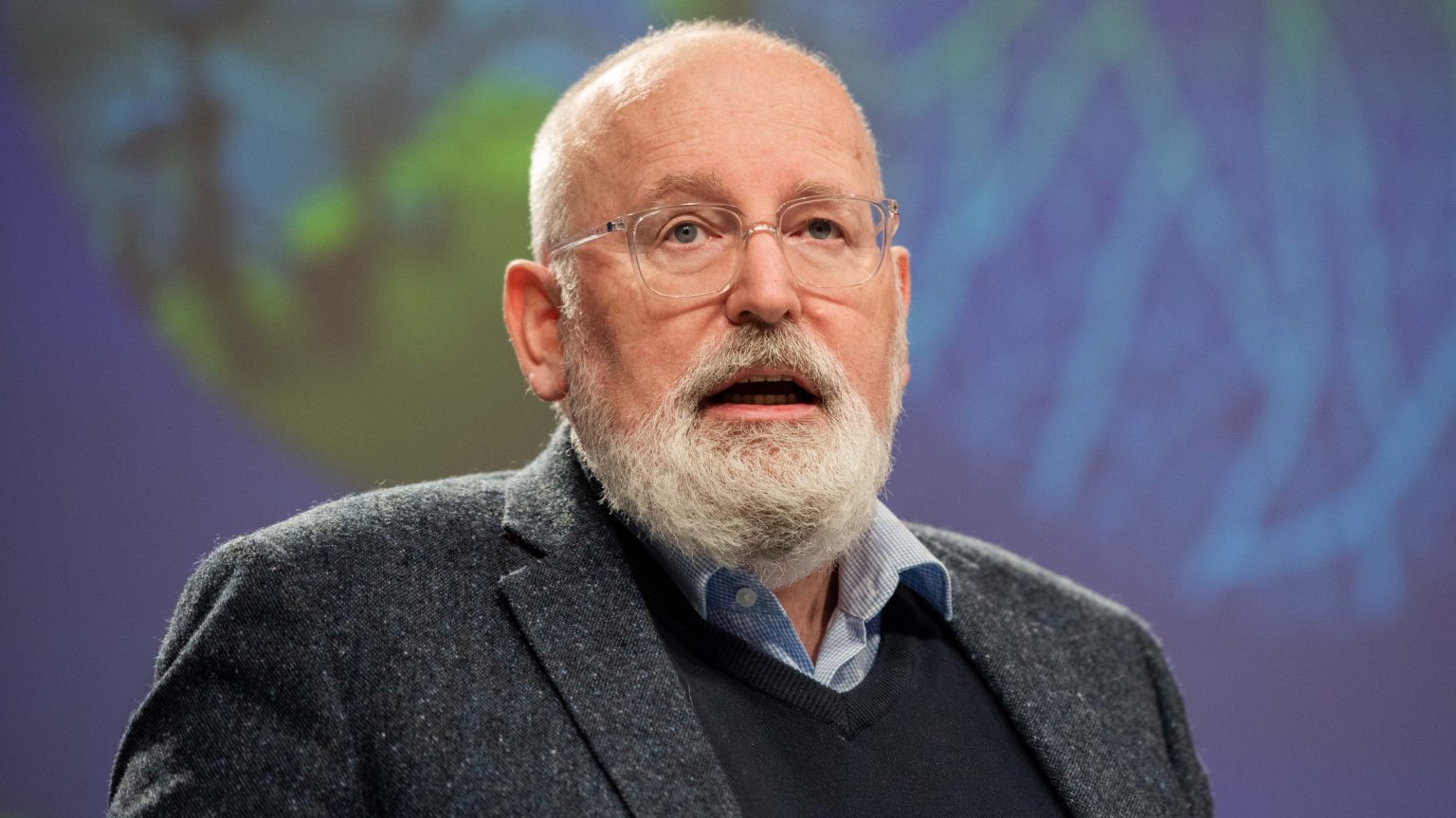

“Carbon removals are an important tool in our toolbox,” said EU Green Deal chief Frans Timmermans. “Capturing CO2 from the atmosphere and storing it for the long term is indispensable if you want to achieve climate neutrality by the middle of the century,” he told a conference about carbon removals organised by the European Commission last month.

There are three ways of doing this: taking carbon out of the atmosphere and permanently storing it underground, storing it in nature, like in trees and soil, and recycling emitted carbon back into products.

In the European Commission’s eyes, all of these are potential ways of reducing the level of carbon in the atmosphere in the run up to 2050 and of balancing out residual emissions post-2050.

“We need to fire on all pistons if we want this to succeed,” said Timmermans. “We don’t have the luxury to set aside any solution that we can find. So we need to use every opportunity to take carbon out of the atmosphere.”

To reach net zero emissions by 2050, the Commission estimates that EU greenhouse gas emissions would need to drop by 85-95% compared to 1990. And carbon removals, it argues, can fill the gap to reach 100%.

The amounts are not negligible. According to a Commission paper on sustainable carbon cycles published last year, those will need to represent several hundred million tonnes of CO2 out of the atmosphere every year.

In the mid-term, carbon removals would be achieved via “the enhancement of the natural sink” such as with afforestation and reforestation initiatives, carbon farming, restoration of peatlands and long-lasting bio-based products like wood used in construction.

In the long term, nature-based removals will be supported by “the deployment of industrial solutions able to capture and store CO2 permanently”.

Technology-based solutions – what the Commission calls ‘industrial solutions’ – include capturing carbon from the air (direct air capture) and capturing carbon from emissions. Both methods then store the captured CO2 permanently underground.

Other options could even create net negative emissions, like Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) where biomass is burnt for energy and the resulting emissions are permanently stored.

Planning for net zero

The European Commission is approaching carbon removals in two stages. In the 2020s, it is focused on setting up a framework for certifying carbon removals and gathering information about them.

Up to 2030, the European Commission sees nature-based removals doing the heavy lifting. In proposals put forward last year, the EU executive aims for 310 million tonnes of CO2 to be captured by nature in 2030 – an increase from the projected 225 million tonnes under a business-as-usual scenario – and 5 million tonnes to be removed by technical solutions.

Beyond 2030, a lot is still to be decided. By 2050, the European Commission foresees the need to sequester several hundred million tonnes of carbon, both through natural sinks and technical solutions. This will include removals of at least 300 or 500 million tonnes of CO2 from technology-based solutions, according to the EU’s scenario planning.

But it’s not clear yet what balance will be achieved between technical- and nature-based solutions.

“We still need to understand much better all the solutions that are out there, their robustness, their credibility,” a Commission official told EURACTIV.

“Today, it’s almost impossible. Nobody could give you the exact specific balance between net removals from nature-based solutions and from technology-based solutions. Because it’s so dependent on many different variables,” the official explained.

One of the problems that makes legislating on carbon removals so complex is that there are still many unanswered questions. For instance, it is not yet clear how many emissions will be left after 2050 and from which sectors they will come. The assumption for now is that the agriculture sector and parts of industry will continue to contribute to those residual emissions.

The elephant in the room is how to determine which sectors will be allowed to continue producing residual emissions, according to Eve Tamme, managing director at the policy group Climate Principles.

“Ideally, it would have been better to start with a carbon dioxide removals strategy on the European level that establishes all these different principles or rules: that we have the separate targets, what it actually means in practice, what kind of residual emissions we are aiming for and who should be doing the heavy lifting on removals,” she told EURACTIV.

Funding removals

How to pay for such carbon removal projects – both technology-based and nature-based – is another question that is only just beginning to be answered.

For technical solutions, the European Commission sees the Innovation Fund appended to the EU carbon market as the prime source of funding.

For nature-based removals, there are ideas to use money from the common agricultural policy to incentivise landowners to store carbon. Alongside this, the European Parliament’s negotiator for the land use regulation, Ville Niinistö, wants to use revenues from the EU’s emissions trading scheme to incentivise carbon sequestration.

Markets are another potential source of revenue and they are already beginning to spring up. Sweden, for instance, is planning a reverse auction of two million tonnes of negative emissions and the Dutch Rabobank has created one of several voluntary markets for carbon removals.

But this patchwork of carbon removal purchasing lacks one vital thing: certification at the EU level.

The European Commission is looking to bring in a certification scheme for carbon removals at the end of the year. This is widely seen as the cornerstone of creating credible and reliable proof of removals.

“Whatever model [of funding] you choose, what you need first is a credible certification,” said a Commission official.

“You need to know for how long, how many tonnes of CO2 are stored and what are also the possible negative effects, like on biodiversity, so you need to put in safeguards,” the official explained.

The EU executive needs to bring forward a robust certification that tackles the issue of permanence, said Mark Preston Aragonès, a policy officer at the NGO Bellona Europa. The Commission should focus on certifying “properly, not quickly” and use the time up to 2030 as a learning curve where mistakes can be easily fixed, he told EURACTIV.

Ultimately, this could lead to a carbon removal market, similar to the EU’s emissions trading scheme. But this is something far down the road for the European Commission, which is focusing on first creating its certification system to build transparency and credibility.

Barriers to certification

Despite the clear importance of certification, there are still hurdles that the European Commission needs to overcome.

Firstly, nature-based solutions are not permanent and will require some sort of monitoring.

“For instance, what happens if a certified forest sink goes up in flames?” asked Artur Runge-Metzger, director at the European Commission’s climate department. “The legislation will have to be able to deal with such a situation in order to make sure that, at the end of the day, there is a physical removal for each certificate – or currency – that has been issued,” he told EURACTIV in an interview back in October 2020.

This issue of permanence is at the centre of concern for policymakers. “There is always a risk of reversal and that the CO2 is going back to the atmosphere,” said a Commission official. “We have to minimise this risk and to also establish liabilities in case of reversal. You need to be very careful on the measurement and on the uncertainties that you have with the carbon removal that you want to certify,” he explained.

Despite those difficulties, Timmermans believes a calculation method can be developed in order to deal with the issue of permanence. “If we can come to a method, a robust method of certifying carbon removals, then I think the issue of permanence will also be dealt with,” he said.

Another key issue is to come up with an accounting system that prevents carbon removals from being counted twice.

“We should have a rigid accounting system that shows that carbon sinks are increasing in the natural world and then that creates a mechanism of social acceptance and support for the bioeconomy solutions that come within that frame,” said Ville Niinistö, the Parliament’s negotiator for the land use regulation.

“If that frame is solid, then whatever happens within it can be with good conscience sold as being environmentally friendly,” he told EURACTIV.

It is yet to be seen how such a certification scheme would be designed. One thing that seems certain, however, is that this would be an EU-level system.

“We would definitely be looking into creating a level playing field across Europe. So I think we should have all the same principles, and the recognition of certain methodologies across the EU,” a Commission official told EURACTIV.

Reductions versus removals

While most believe that removals and reductions will both be needed if Europe wants to reach net zero emissions, there are concerns that focusing too much on carbon removals could give polluters an out.

Using technological fixes and neglecting to tackle the overconsumption and overuse of natural resources that are driving the climate crisis will not be enough, Niinistö told EURACTIV.

The European Commission is well aware of this issue and says that emissions reductions are its “first priority”. Ideally, reductions and removals need to go hand in hand, it argues.

“We need to start by not putting [carbon] into the atmosphere. But even if we stopped putting it into the atmosphere, there’s still so much carbon there, it will need to be taken out as well,” said Timmermans.

“You can never say well, technology will solve everything and, you know, we can sit on our hands, waiting for technology to solve everything – that is completely irresponsible,” he added. “But at the same time, we’ve also seen investing in new technologies does bring huge positive results,” he continued.

To prevent this kind of “moral hazard”, some suggest reserving access to the market for carbon removals only to those who can prove they’ve done their share in reducing emissions.

“There could be rules in place that you really have to qualify to be able to use removals. So you have to reduce your emissions to a certain level before you can start using removals,” said Tamme.

According to her, this is why it is crucial to have separate targets for carbon removals and reductions. When the European Commission first suggested its more ambitious 2030 emissions reduction target, it faced criticism for creating a ‘net’ target that blurred the line between reductions and removals.

However, it later clarified that the role of carbon removals would be limited to 225 million tonnes of CO2, capping the reliance on removals.

The narrative around carbon removals also needs to shift from being driven by demand to being driven by the realistic amount of removals that can be supplied, according to Preston Aragonès.

“We need to be really wary of the hype,” he told EURACTIV.

“Buying an offset shouldn’t be seen as ‘check me out – I’m carbon neutral. I bought offsets’. It should be seen as shame in the sense that ‘I’m still emitting. So I have to offset’,” he explained.

The European Commission is also guilty of this overreliance, according to Preston Aragonès. He warned that the idea that negative emissions could just “fill the gap” without considering the barriers preventing this can lead to numbers which are “quite heavily inflated”.

Original article from EURACTIV.